The late 19th century was the golden age of Scandinavian painting. Among the most famous were the Skagen painters: mainly Danish artists gathered in Skagen in northern Denmark, drawn by the summer light. They painted local fishermen, the scenery and – famously – themselves. It’s a very human and endearing trait. We create our tribes and we celebrate them. We want our fleeting connections memorialized. See the category Wikimedia conventions on Commons: its subcategories have thousands of photos of maybe questionable educational value. But they depict us. Not as disconnected individuals but in the context of our tribe of information gatherers and knowledge disseminators. To us, that has a value.

There’s very little we can’t create a tribe around. The literature we know as science fiction – the stories categorised as such when published – was, in English, for decades developed somewhat isolated from most the rest of the literary field. On the one hand, it was disdained and ridiculed as the worst kind of pulp fiction, on the other hand, it had a number of acolytes who took it very seriously. This created a ghetto were science fiction nurtured its own writers, readers, editors, magazines, publishers, even its own literary norms, where ideas and speculation were in focus and style and psychology were relegated to the sidelines. Around this a sort of readers movement, known as science fiction fandom, came to play a vital role. The line between fan and professional was porous: many writers, editors, critics – and in countries outside the English-speaking world where translated fiction is a normal thing, translators – came from the ranks of organised readers and might have started out writing for or editing fanzines. Not that everyone did, but it was a fertile seed-bed, having a role in bringing up writers such as Isaac Asimov, Judith Merril and Ray Bradbury.

But no ghetto lasts forever. The walls started breaking down, from the 1960s and onwards science fiction as literature aligned more closely to the values of other kinds of fiction, and as it normalised in other ways, the paths into a professional career came to look more for the rest of the literary field as well. Still, science fiction fandom kept – and keeps – playing a more central role than almost any other group of readers. It gives out central awards, does important literary criticism, organises events, it has a voice.

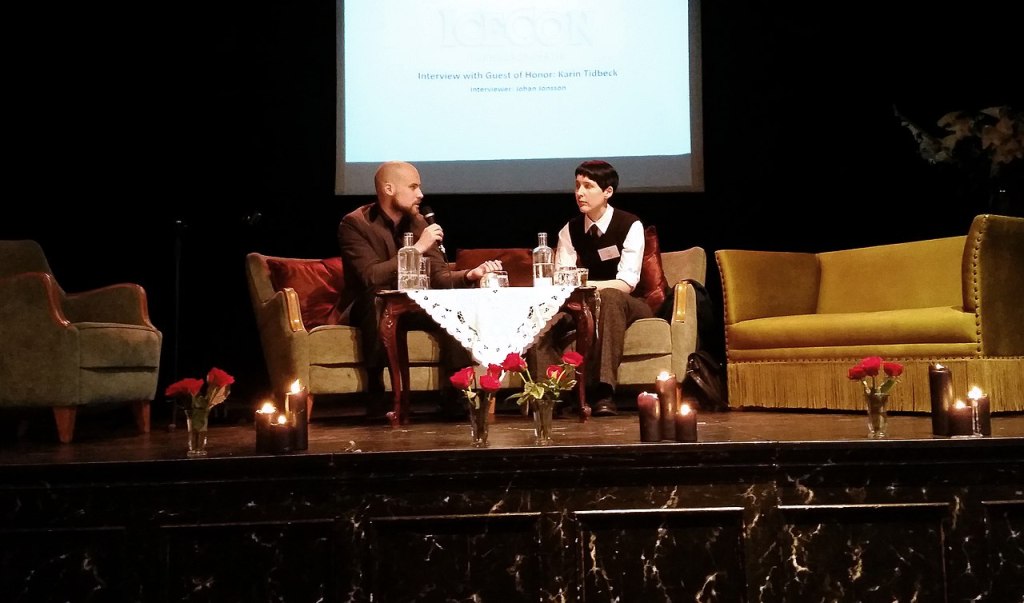

The literary science fiction and fantasy convention – as it has come to typically focus on both these forms of literature – is a mix between a conference and a literary festival. They have been organised since the late 1930s and have a focus on panel discussions, presentations, interviews and the occasional reading. Compared to the typical literary festival it is less of a chance for readers to listen to their favourite writers and more of a celebration of the literary forms: it’s entirely possible to organise one without any professional writers at all. But it is, still, your best chance to find a collection of people who’ve made an impact on the field. Who are notable.

Going to a science fiction convention can be remarkably like going to for example Wikimania, the main annual Wikimedia event. The science fiction convention – including the one called Worldcon – is less international, with fewer nationalities and typically has a heavy focus on participants from the West, and has less of a feeling of working together towards a common goal, but has the same feeling of being in this together, the same tribal background radiation. For both the Wikimedia movement and science fiction fandom I’ve been asked to host strangers on my couch, sort of the way you might be asked to help a distant cousin you’ve never met: They’re one of us, you know.

I don’t normally photograph people. My thing is buildings and that’s what I’ve got the equipment for. But Wikimedia Sweden has pool of technology, where anyone who wants to create some sort of media for Commons can borrow a microphone, camera or whatever they might need and suddenly one of my habits in life is to exchange suitcases full of equipment by way of the luggage lockers at the Stockholm Central Station, something which previously was part of my life mainly in the form of thriller movies and novels of questionable quality. This comes with all the drawbacks of experiencing life through a lens – but one should not underestimate the value of having something else to do when a programme item veers into the territory of boring. Thus I can illustrate articles about writers, translators, editors, magazines, publishing houses, critics and not least articles about science fiction and fantasy fandom and conventions.

I used to be rather conservative in regards to my uploads. Why do I want to upload this, can I use this in a article, for which reason am I uploading this particular photo? But I’ve learned to appreciate the rich donations of images uploaded to Commons without necessarily knowing exactly why this or that particular photo was uploaded other than that the setting had an education value. And so I’ve taken this to heart: I don’t upload directly unflattering images, I avoid too personal situations, I don’t upload photos of inebriated persons, I don’t upload close portraits of random convention members, but otherwise try to give a broad coverage also of the event itself.

As a Wikimedian, I much prefer these photos to relying on images released by publishers or agencies because it suits their purpose – a purpose which isn’t necessarily the same as ours. The slick, heavily edited photographs gives a distorted view of reality predominantly aimed at selling books. These are usually very nice photographs, of much higher quality than most of what I can offer, but ignoring the rhetorical value of an edited image is – I would argue – a neutrality concern. We shouldn’t be blind to what an image is trying to express, much like we don’t simply accept companies or persons presenting themselves in flattering manners in text.

My photos alone would probably be enough to give the science fiction and fantasy scene better image coverage on Wikipedia than any other Swedish literary niche we write about. But one is rarely alone in life and building an encyclopedia is to be a very small cog in a very big machine and so I’ve recruited a good number of my non-Wikimedian friends to help me in various ways. Henry Söderlund is a professional photographer – far more skilled than I am – and regular at Finnish science fiction conventions, he uploads his images from conventions such as Finncon or Åcon under a CC BY license, which is a cruel thing to do since it creates an itch that won’t go away until I’ve taken the time to upload anything useful to Commons. A couple of hundred Wikipedia articles and Wikidata items use his photos. PC Jørgensen has taken the time to upload a number of photos from various conventions going back to the 80s and released them under a CC license.

This is easy, of course. Anyone can upload these photos. They’re available and they’ve got a compatible license. It’s when others take photos and have nerve to upload them without releasing them under a sufficiently permissible CC license I turn into a terrible friend. Poor Johan Anglemark will get a ping whenever I look at one of his NC-licensed album and find a number of images I could use. It’s up to you, of course, I tell him, but I’d appreciate if you’d could potentially imagine to possibly scrap the NC part for this particular album in the name of free knowledge, I tell him. The world will be forever grateful. And he does, although most the world has probably largely forgotten fairly soon thereafter. Anna Bark Persson made the mistake of admitting to having a number of useful images from Icecon in 2016 and made vague promises to upload them at some point. When she visited me for a couple of days I literally sat her down in front of my computer to create an account and upload the photos, which I had downloaded in preparation of her visit.

Not only does this mean we get a pretty good coverage of Swedish and Finnish literary science fiction and fantasy. A disproportionately large number of US and British writers in the field have the photographs illustrating their Wikipedia articles taken in Sweden or Finland.

To some degree I have an additional goal. These are memories of one of my tribes, precariously spread out. The internet is a forgetful place. Sites get taken down. Servers fall asleep never to waken again, their services no longer needed. Everything not saved will be lost. By uploading at last the photos I believe have some sort of relevance outside of our culture, for their ability to illustrate the persons whose likeness have been captured therein or merely to explain the phenomenon itself, I try to store a little bit of those memories somewhere else, too, hoping it might save them a little bit longer.

This I have learned: most of my friends have nothing against releasing their images as CC BY or CC BY-SA if they’re given a good reason to. They’re not professional photographers, or if they are, they’re aware they’re not going to make any money from these particular images not being freely available for use on Wikipedia. They just don’t want to sit down and upload things to Commons. This is where I always fail. A good number of times I’ve extracted a promise of future uploads only to – as expected – wait in vain for the images to appear. Editing the Wikimedia wikis isn’t their hobby. They will always have something else they’d rather do. But they don’t mind helping out, as long as they don’t have to do much.

As long as the doing gets done by someone else.

Can you help us translate this article?

In order for this article to reach as many people as possible we would like your help. Can you translate this article to get the message out?

Start translation